Canada’s housing crisis is often discussed in absolutes: either prices will crash, or they will never fall; either governments must intervene more, or get out of the way entirely. But when we place recent market conditions alongside deeper structural critiques—like those raised on Angry Mortgage—a more complicated, and more honest, picture emerges.

A Short-Term Opening for Buyers

In the near term, there is a meaningful shift underway—particularly in markets like Toronto and Vancouver.

Sales volumes are historically low. Investor activity has largely evaporated. Pre-construction is stalled. Buyers who remain are mostly end users: families and individuals looking for a place to live, not to flip. This has quietly shifted leverage. Selection has improved. Negotiation is back. Sellers, not buyers, are adjusting expectations.

This does not mean we are at the “bottom,” nor does it mean prices cannot fall further. But for financially stable households—especially first-time buyers who were entirely shut out between 2020 and 2022—this is the most buyer-friendly environment in years.

Yet this short-term opening exists inside a housing system that remains fundamentally broken.

The Structural Problem: Housing as a Government Revenue Tool

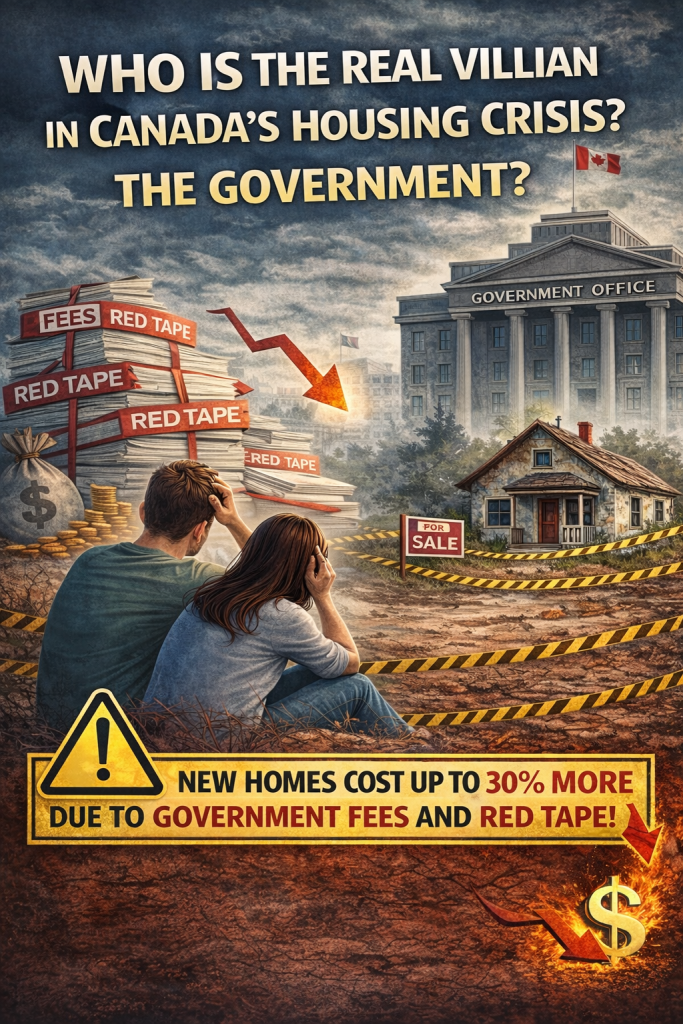

As Ben Woodfinden argued on Angry Mortgage, the most under-discussed driver of unaffordability is not speculation alone, immigration alone, or even interest rates—but government cost-loading on new housing.

In cities like Toronto, as much as 30% of the cost of a new home is made up of development charges, fees, taxes, and levies. These are not marginal costs. They are embedded into the price of every unit, passed directly to buyers, and treated as a normal feature of governance.

Housing, in effect, has been taxed like a luxury good—while being rhetorically framed as a human necessity.

Layered on top is what Woodfinden calls the “Anglo disease”: a regulatory culture that makes building slow, adversarial, and legally dense. Years of approvals, consultant reports, appeals, and political veto points create scarcity by design. The result is not careful planning—it is paralysis.

This is how Canada ends up with 50-storey towers beside single-family zoning, and almost nothing in between.

The Missing Middle—and the Missing Social Contract

What ties these discussions together is not just economics, but expectations.

A generation of Canadians did what the social contract asked of them: education, work, saving, delayed gratification. Yet homeownership now requires top-1–2% household incomes in major cities. The promise that effort leads to stability has quietly collapsed.

That anger is not theoretical. It shows up in delayed families, longer commutes, overcrowding, and a growing sense that democracy responds faster to asset holders than to workers.

When young professionals earning $90,000–$100,000 cannot even imagine owning a modest home, something deeper than market cycles has failed.

So Where Does This Leave Us?

In the short run, today’s market offers cautious opportunity for buyers who are purchasing shelter, not status.

In the long run, affordability will not be restored without structural change:

- Development charges must be rethought.

- Zoning must allow mid-density housing where people already live.

- Speed, not symbolism, must become the metric of housing policy.

More programs alone will not fix this. Nor will pretending the market can self-correct under the current regulatory load.

A Critical Outlook

Canada’s housing crisis is not caused by a single villain. It is the outcome of decades of policy choices that treated housing simultaneously as an investment vehicle, a revenue source, and a political risk to be avoided.

Buyers may find a window today—but unless governments stop profiting from scarcity while promising affordability, that window will close again.

The question is no longer whether housing is broken.

It is whether we are willing to stop pretending we don’t know why.